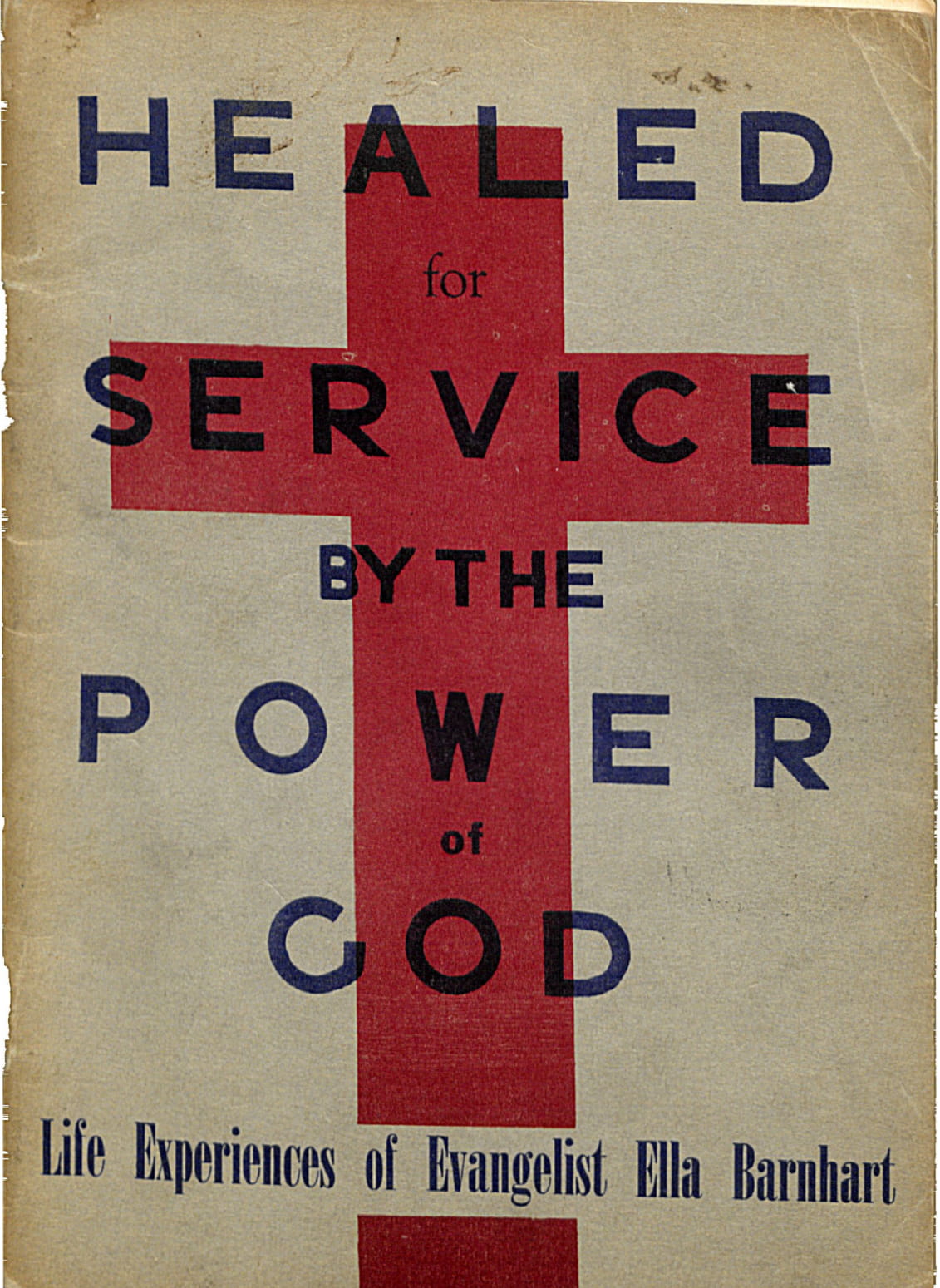

A Door in the Air

(click, then use arrow keys to navigate pamphlet)

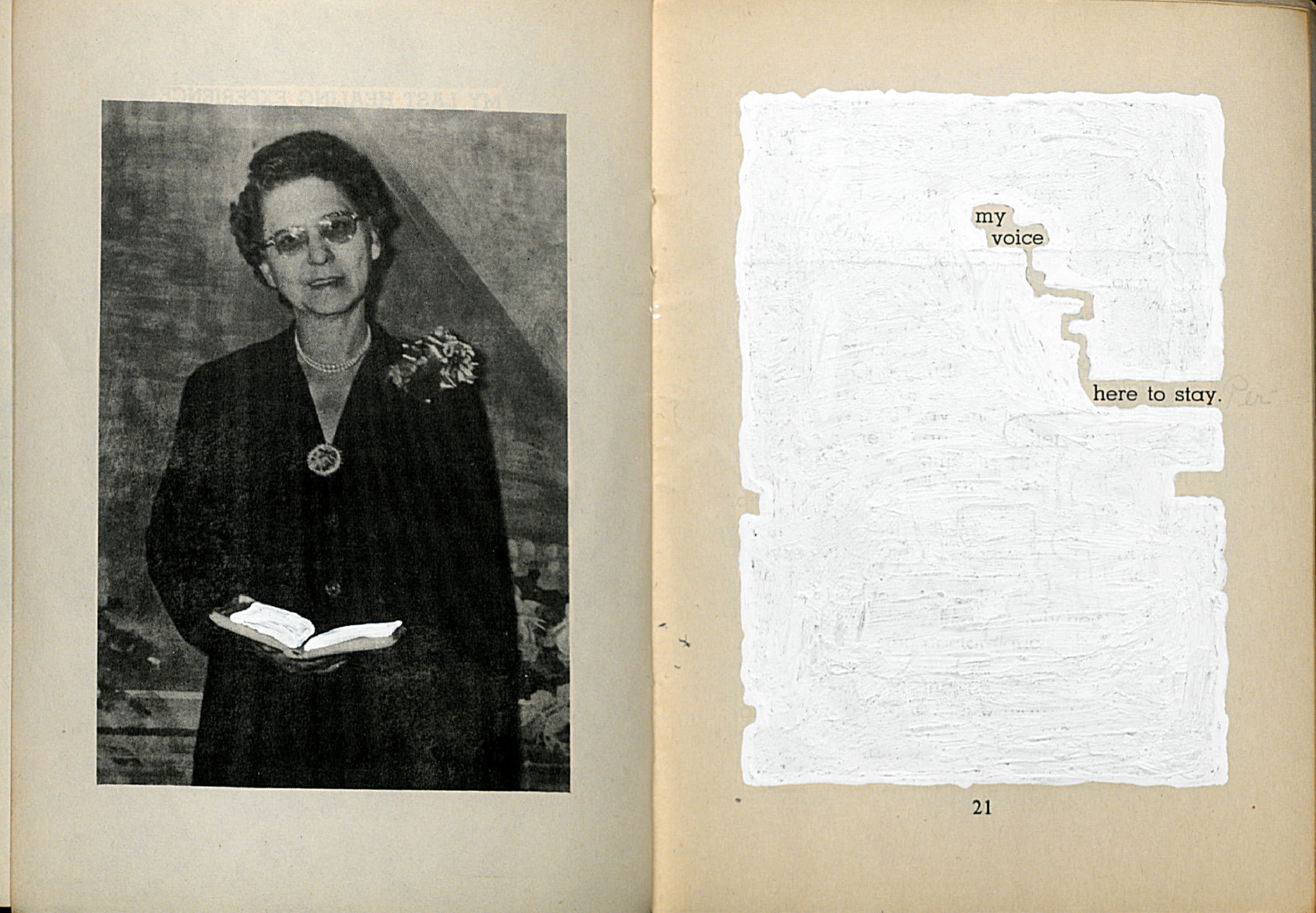

On Erasure

Apparently, there’s a boom happening in the production (or more accurately, deduction) of erasure poetry. I’m surprised to hear this since I don’t personally know a single poet practicing erasure seriously. That could be because I don’t know very many poets, but I think it’s also likely that most poets don’t think of erasure as a genre worth specializing in.

In the past, when I’ve been encouraged to try erasure, it’s as a warm-up activity, something to get the juices flowing before the real poetry begins. The unspoken agreement: erasure is fun, but it’s not going to produce a well-crafted poem, and it’s certainly not publishable.

But the belief that erasure mostly produces bad poems is just a sign that poets are mostly very bad at erasure. And who can blame them? As a poetic form—and I mean “form” in the sense of a physical structure, a patterned system of poetic features like line, diction, sound, rhythm, etc.—erasure certainly invites the kind of lazy, grandiose fragmentation that most critics of contemporary poetry would call pretentious or lacking in craft. Is erasure, like the influx of concrete and open-field experiments encountered by every Intro to Verse instructor, simply a phase that young writers must pass through?

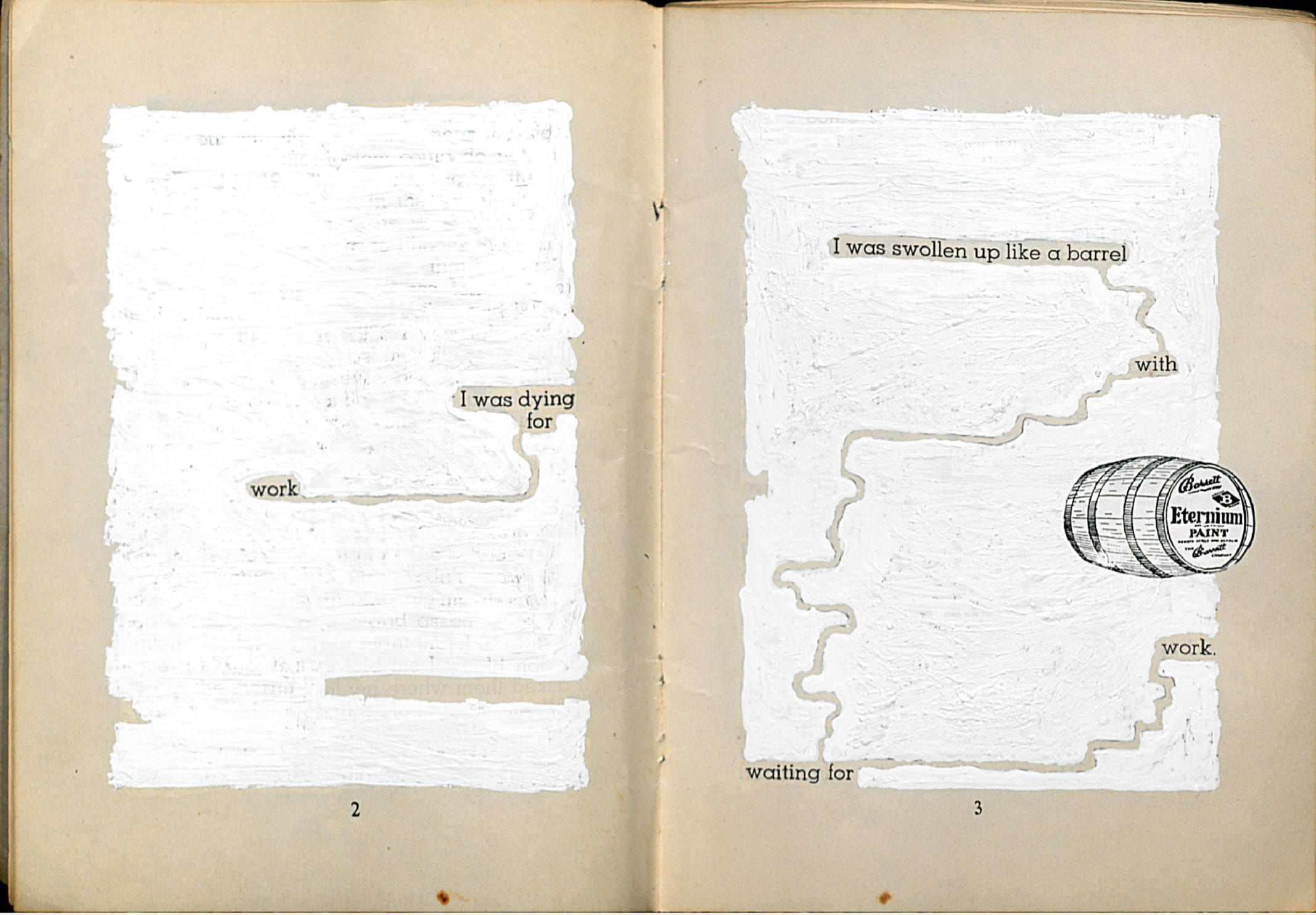

To compound the difficulty, erasure is also prohibitively difficult to sustain through multiple pages of text. You begin erasing on a page that, say, intricately describes a horse in a field, but by the end of the book, the horse never reappears, which is awkward. You begin an erasure of a magazine by working with the language of an advertisement for plastic surgery, and you’re forced to give up four pages later because you can’t link the diction of liposuction to the following article, which is about Anne Frank’s lost diary pages. Naturally, the erasure ends up being a page or two long, which is enough to say, “That was a fun experiment,” but not, “I could make a book out of that.”

Though laziness and fragmentation are unfortunate characteristics of bad erasure, we can easily see how thoughtful practitioners of the form manage to avoid these traps. Mary Ruefle’s book, A Little White Shadow, was my first encounter with an erasure that didn’t read like a grocery list of nouns. Here’s page eight: “Seven centuries of / sobbing / gathered in the / twilight. / and / had their / pages / wandered, / through”. To use Pimone Triplett’s phrasing, Ruefle balances an element of difficulty with an element of unity. We’re accustomed to being challenged as we parse the semantics of a poem, and in Ruefle’s erasure, we’re encouraged to forge on by the apparent sensibleness of the syntax. Creating and maintaining this kind of balance is frequently overlooked in the composition of erasure poems.

Ruefle’s erasures are almost immediately recognizable as poems in their sonic qualities and evocation of image, but they won’t quite behave as poems in the way we talk about them. Should I place the virgule as it corresponds to the way the words are clustered on the page, or should it honor the original line of prose? Another way of quoting the same passage might be, “Seven centuries of / sobbing / gathered / in the / twilight. / and / had their / pages / wandered, through”. The difference may seem slight, but it would certainly result in a difference read aloud. And how do we incorporate the pages that come before and after? Our understanding of “wandered, through” certainly changes when we know that the first words on the next page are “the dead.”

One way the erasure is functioning for Ruefle is to expand the ways the poem defers and multiplies meaning. Is a single page of erasure more like a stanza, or is it more akin to the poetic line? Both stanza and line can work to create meaning, argument, or logic; both can bridge into another space, complicating or expanding upon that meaning. Section, segment. Define, defer. The separations in an erasure make us ask the same questions as line breaks and stanzas, without fitting neatly into either category, thereby troubling the essential building blocks of poetry. Maybe we should call it all caesura.

–

Here’s another question I’d genuinely like to know the answer to: Are erasures poems?

Maybe erasure is some incarnation of the experiments with concrete poetry that Rosmarie Waldrop describes as a revolt against the transparency of language, a way of forcing ourselves to acknowledge the material, instead of just looking through the word to find its meaning. Or maybe erasures are simply a form of visual art—a kind of lazy painting that exploits the faux-forcefulness of words scattered on a page. Which category do I use in Submittable?

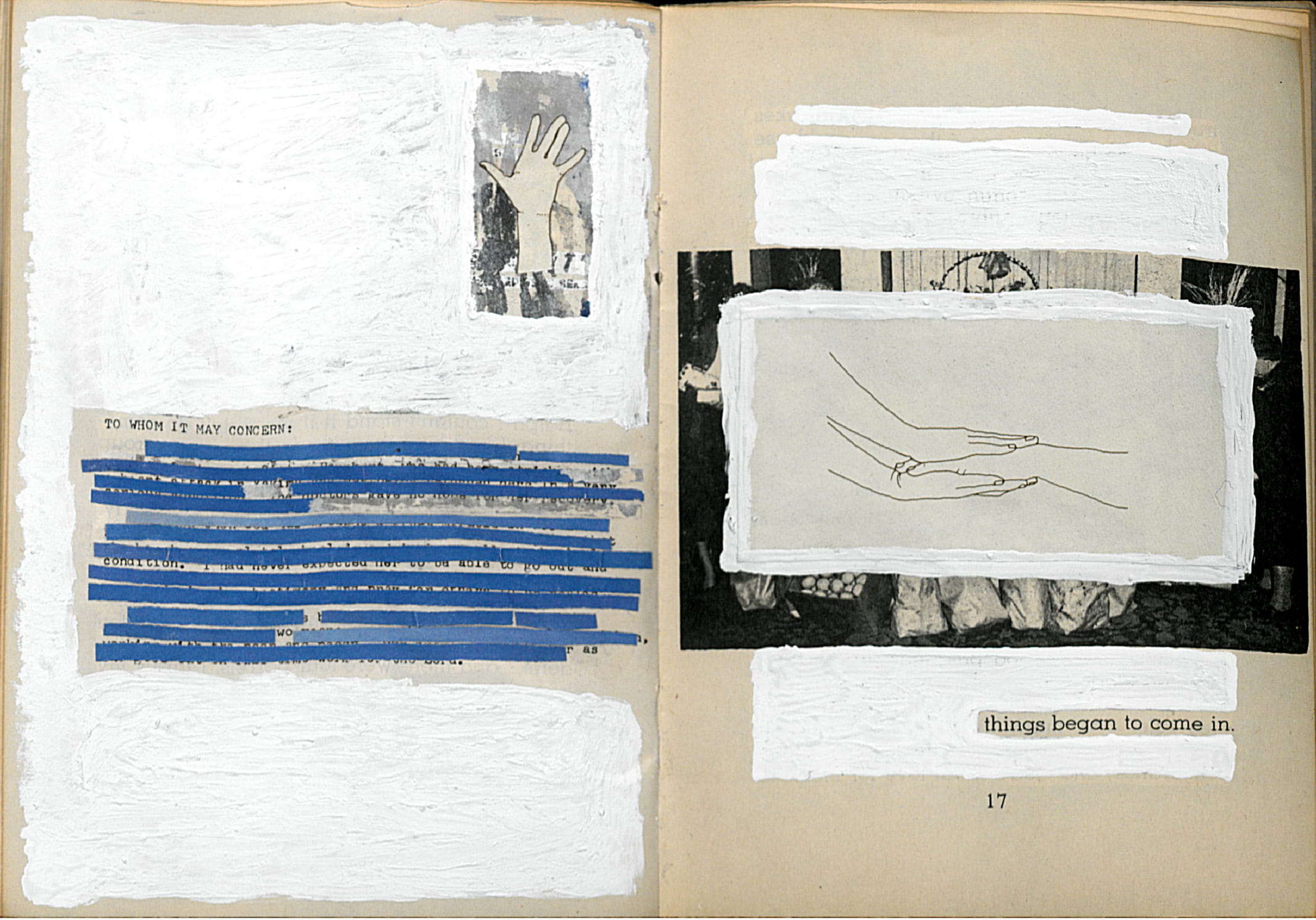

In an interview, Doris Cross repeatedly rejects the idea that her erasures of dictionary pages are poetry. She insists that she is only “making connections,” and then later, perhaps more accurately, “looking for connections.” But when the interviewer asks if her erasures are primarily visual objects, Cross rejects that idea too. “Sometimes it's involved with sound,” she says. “I'm dying to find someone to do music to these.”

Cross also says that she won’t add words that aren’t there. She won’t relocate words, either. After all, “An artist has to have rules.”

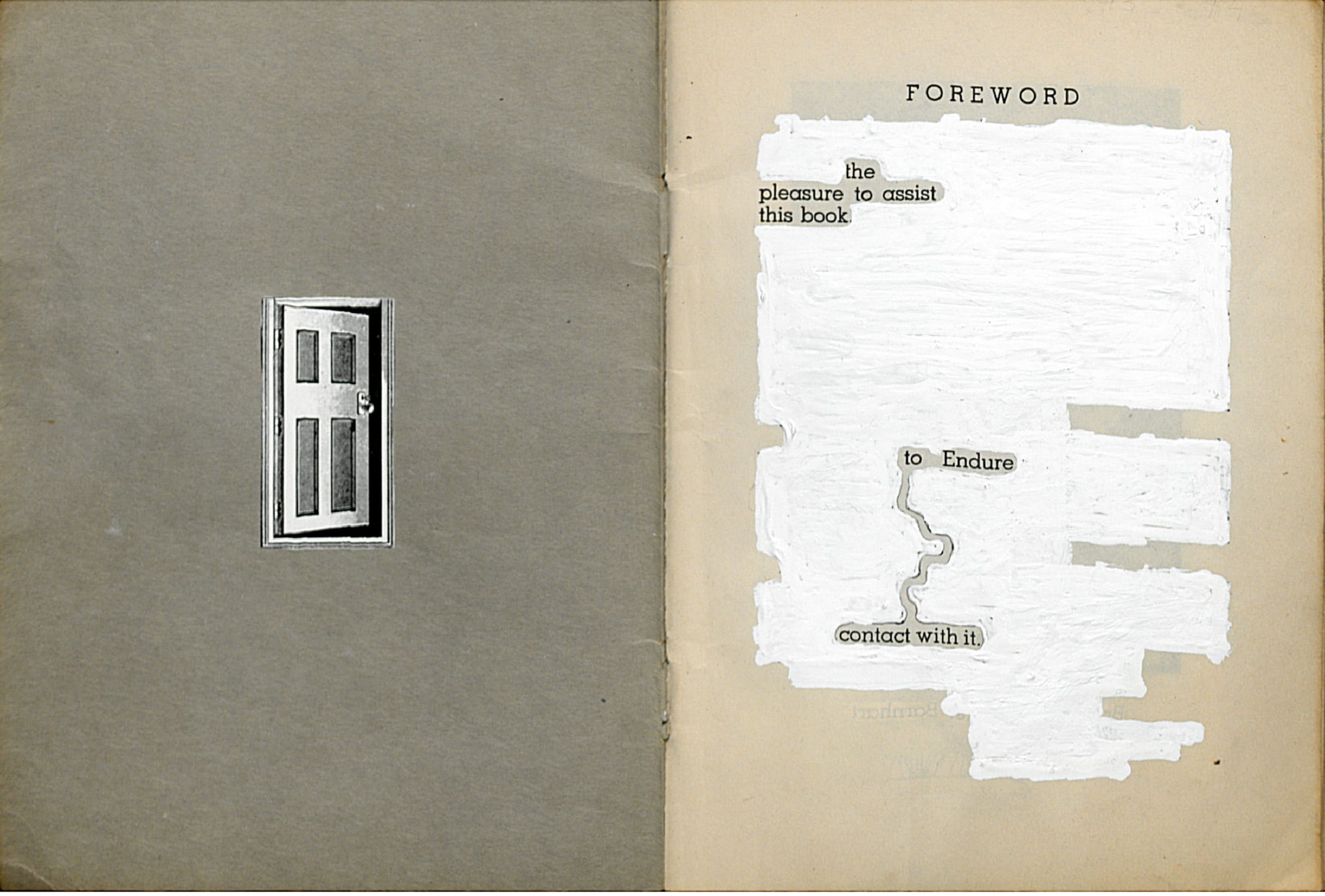

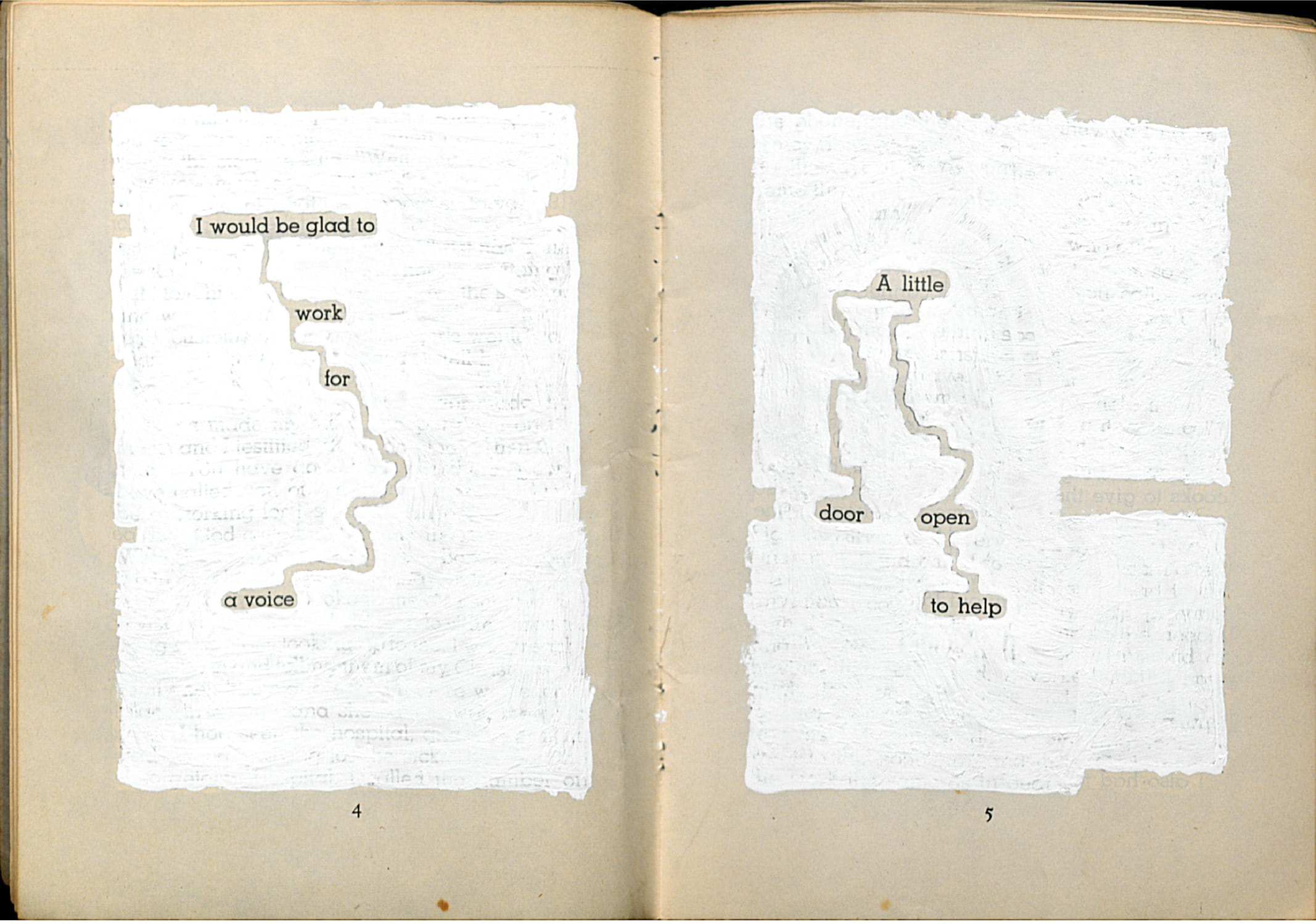

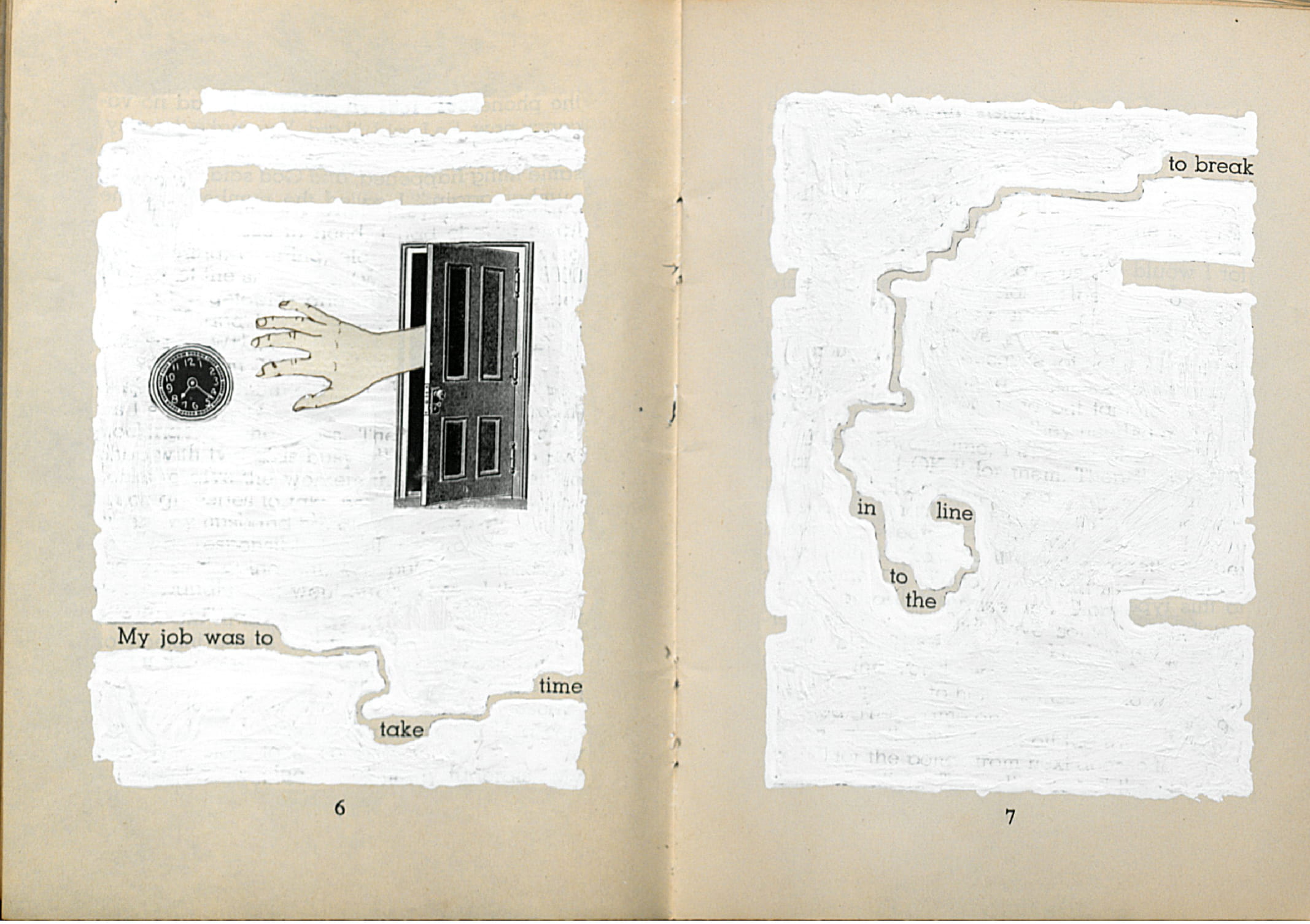

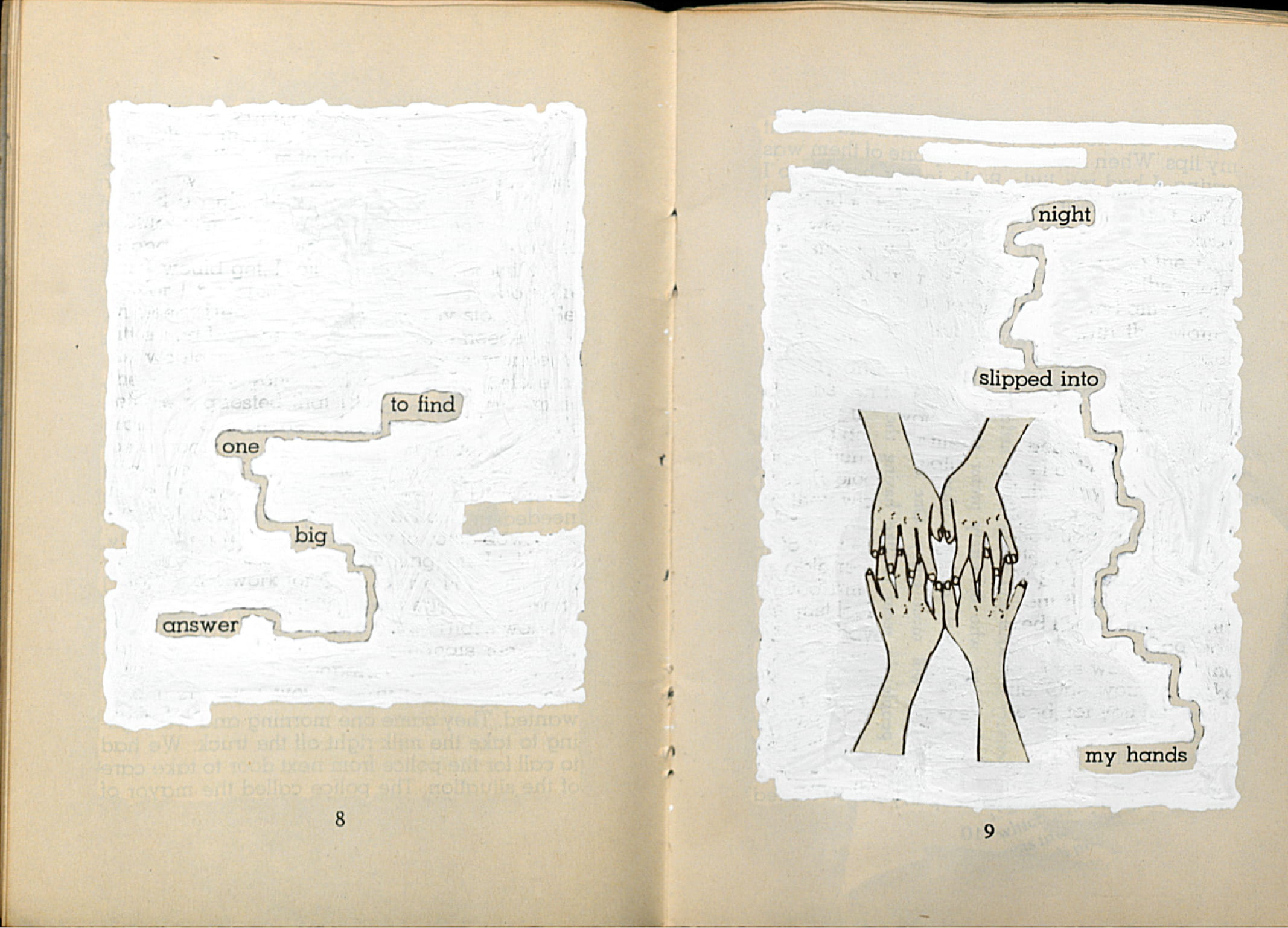

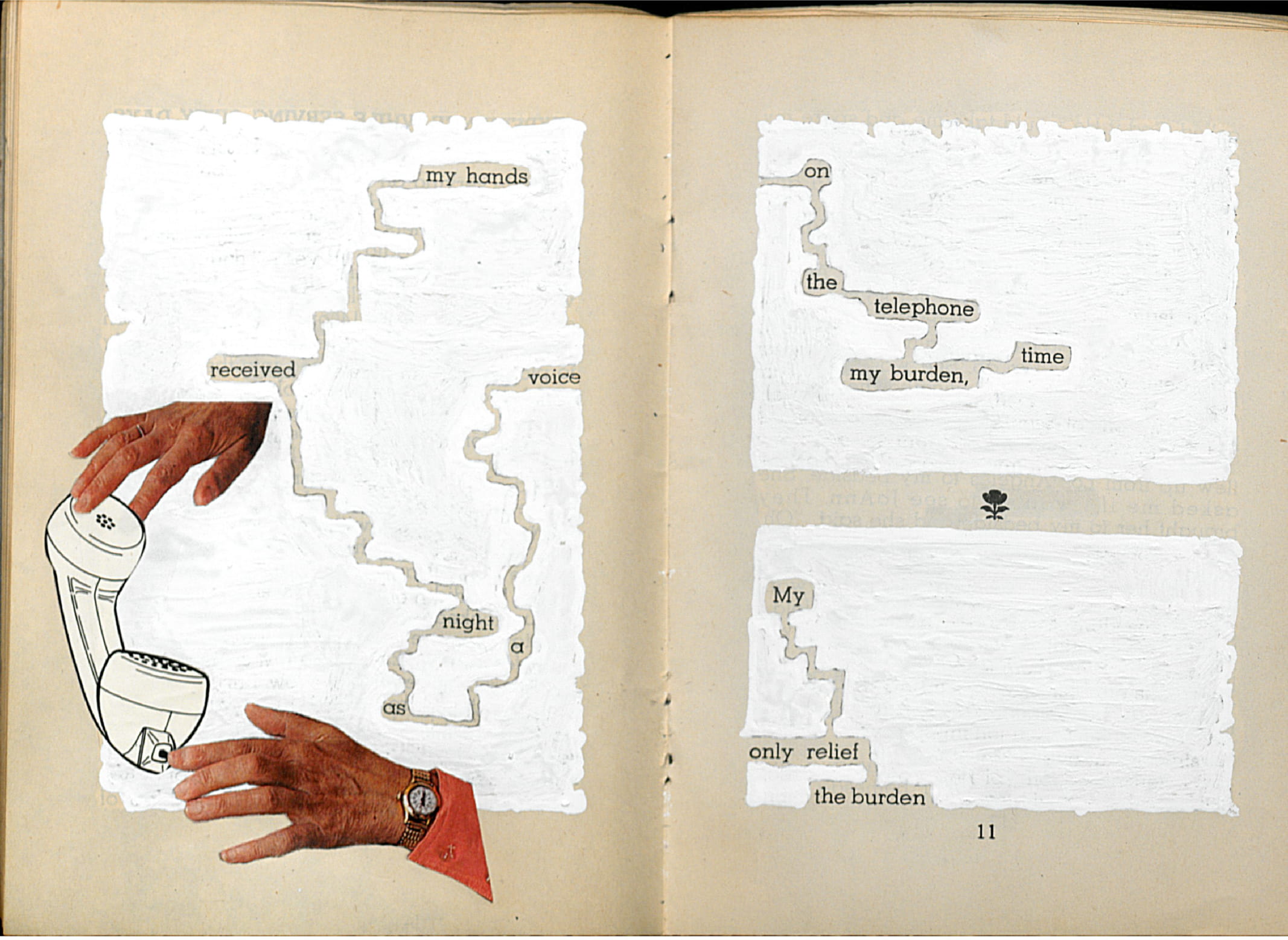

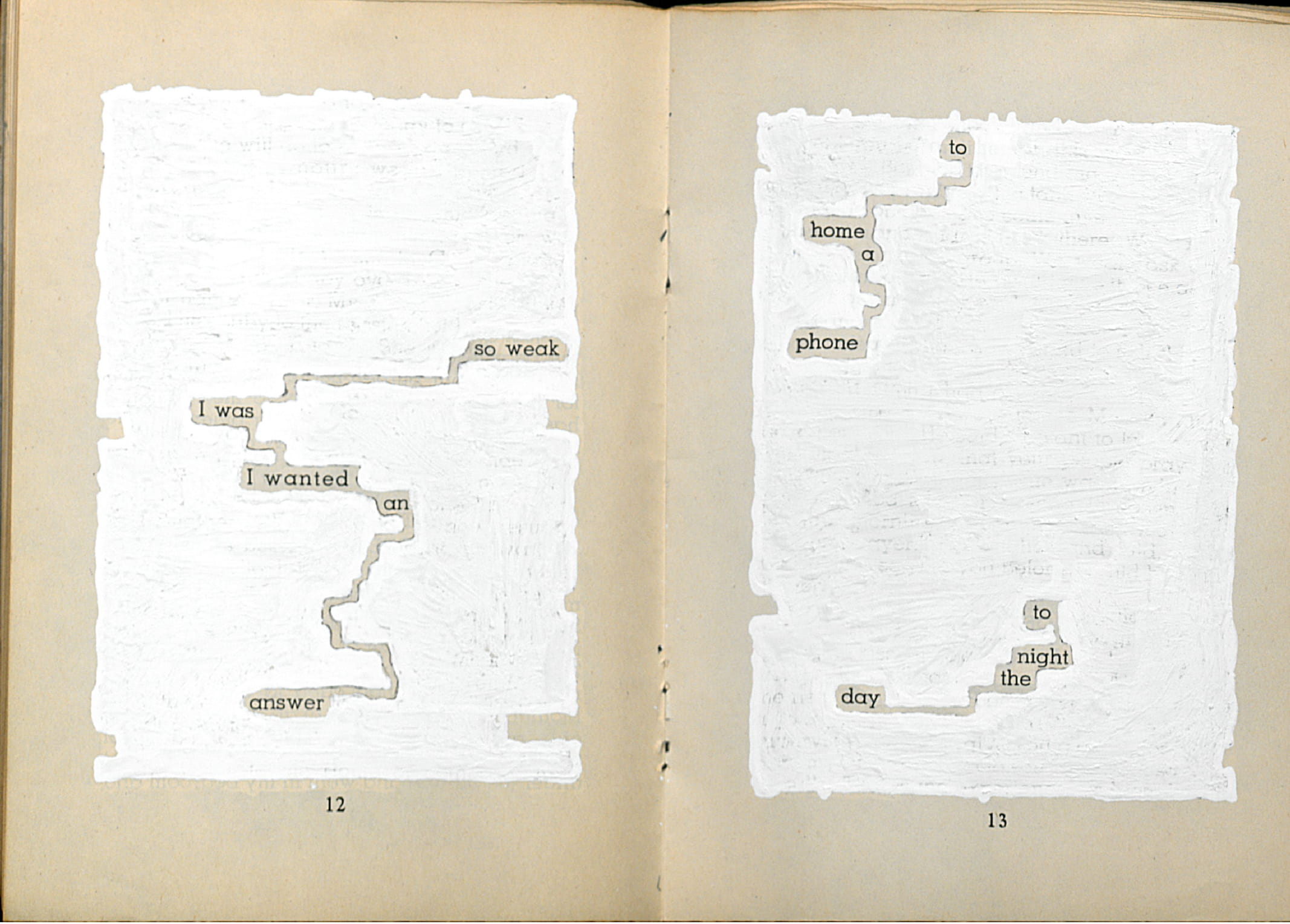

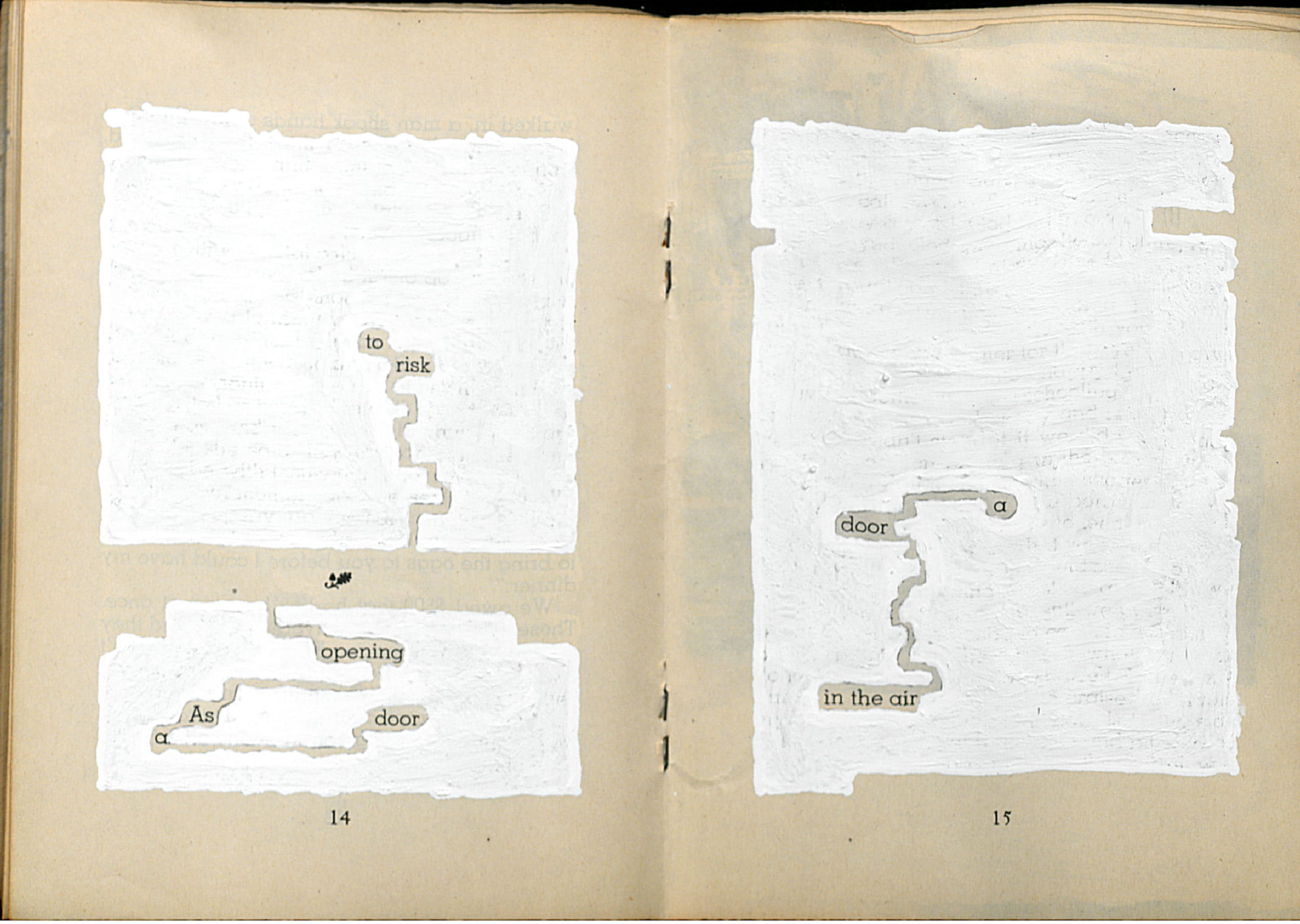

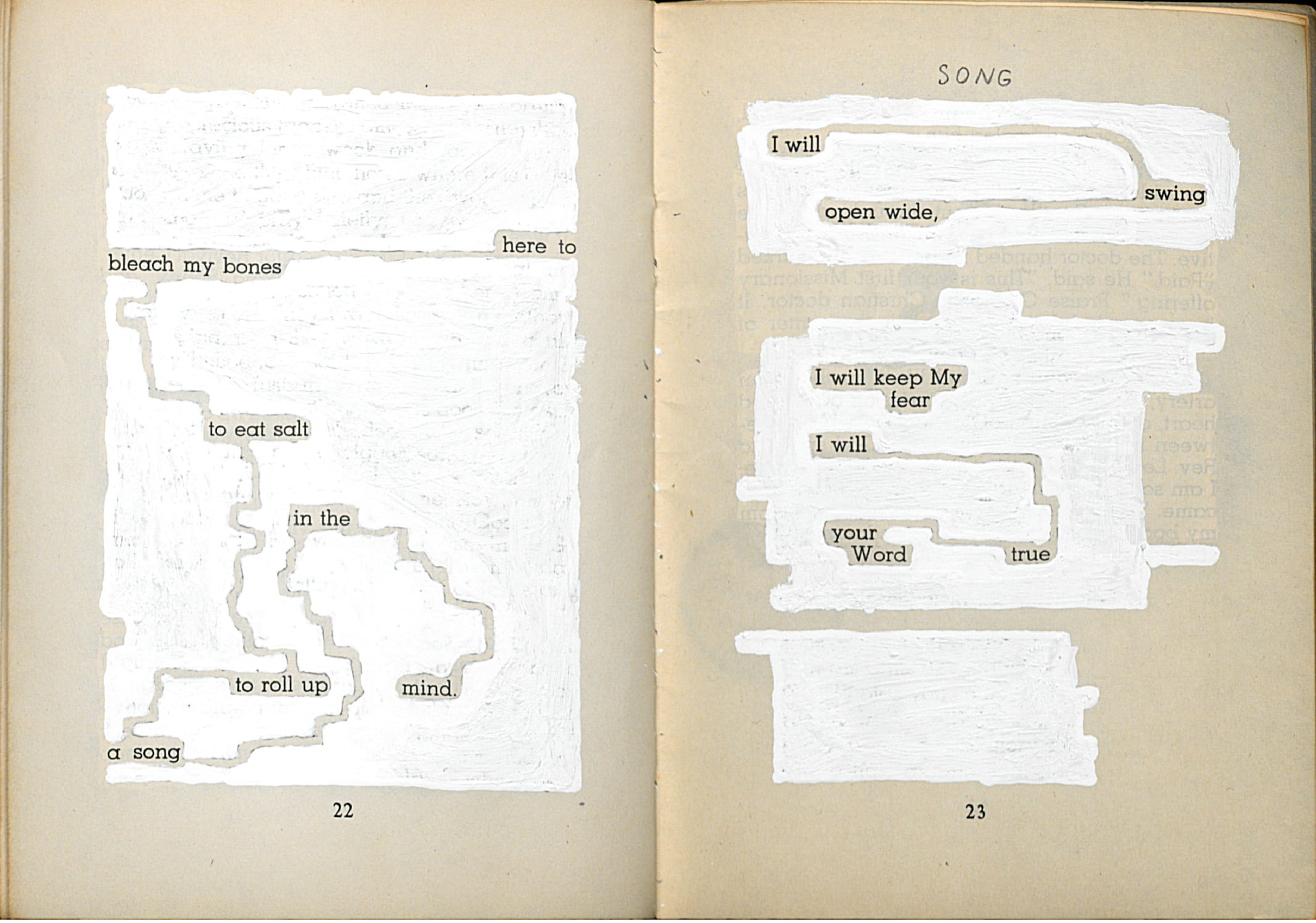

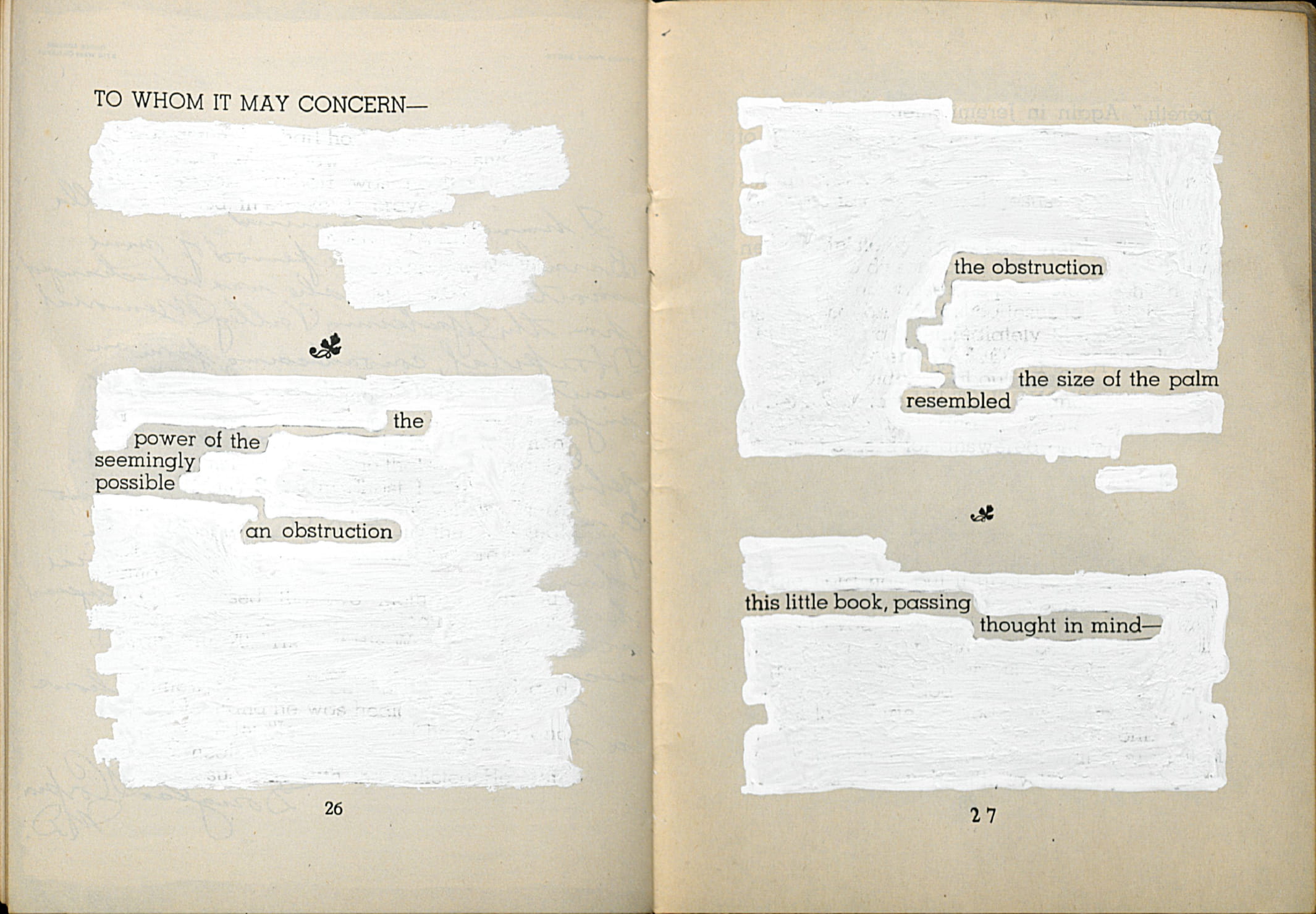

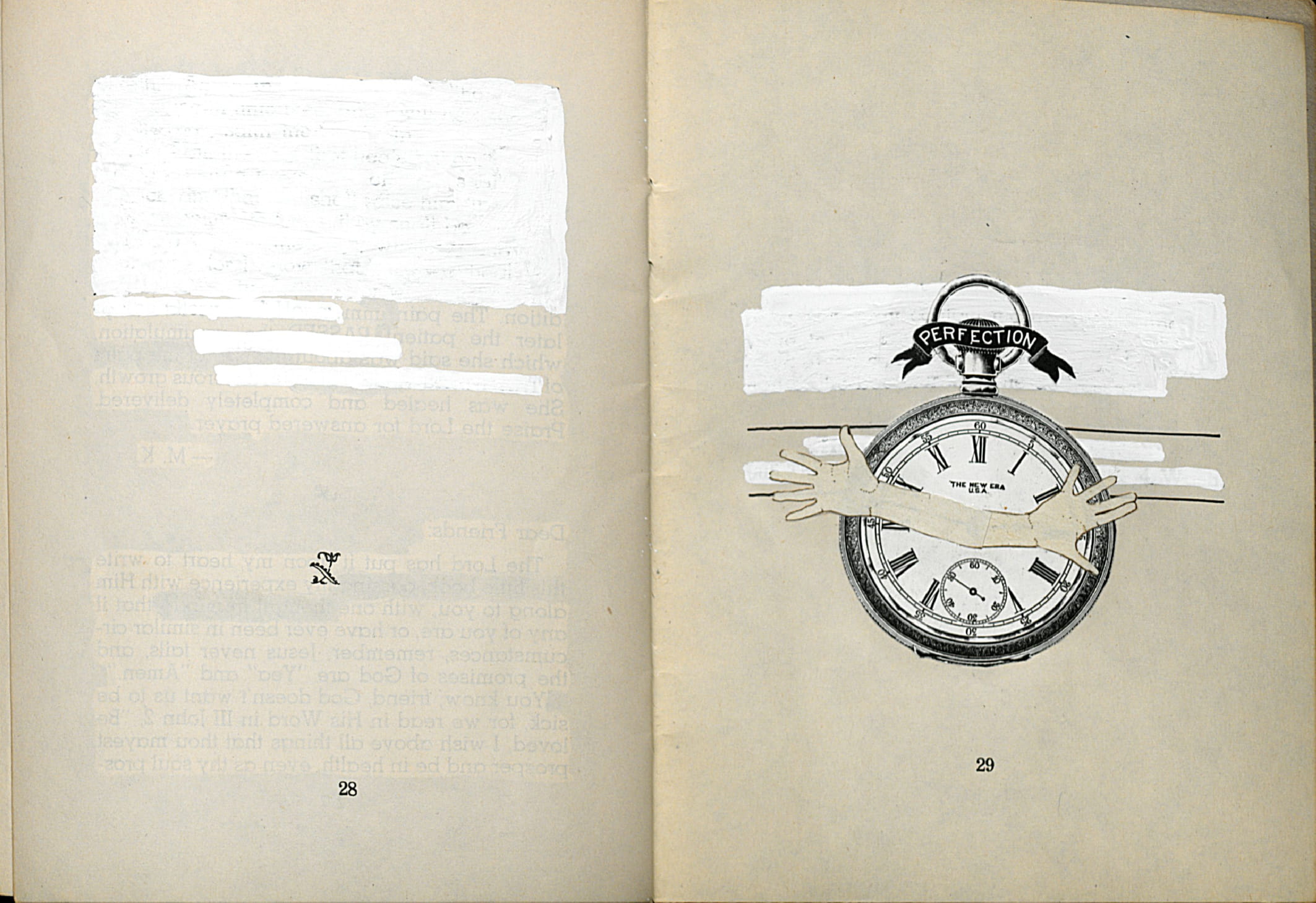

Among the proliferate rules I’ve seen in erasure (I’m sure there are many more I haven’t) are using only white-out, using only black-out, scribbling messily with a writing implement, drawing or painting over the page, cutting parts out of the page, or divorcing the selected words of an erasure from the original page completely. Of all of these, only the last strategy really offends me, as it seems like an easy way to confuse a reader into thinking that what they’re reading isn’t an erasure at all. Let me also say that I’m not such a postmodernist as to think that “erasing the erasure process” is some kind of final, ultimate erasure. That’s cheesy, and I don’t think that’s what erasure is about. And while each of these strategies emerges from the same rule—to remove some of the original words, and by removing, create a new, original utterance—the resulting mood of each strategy is as different as a poem set in Helvetica is from one set in Comic Sans or Papyrus.

–

The Academy of American poets gives this definition of erasure:

Erasure poetry, or blackout poetry, is a form of found poetry wherein a poet takes an existing text and erases, blacks out, or otherwise obscures a large portion of the text, creating a wholly new work from what remains.

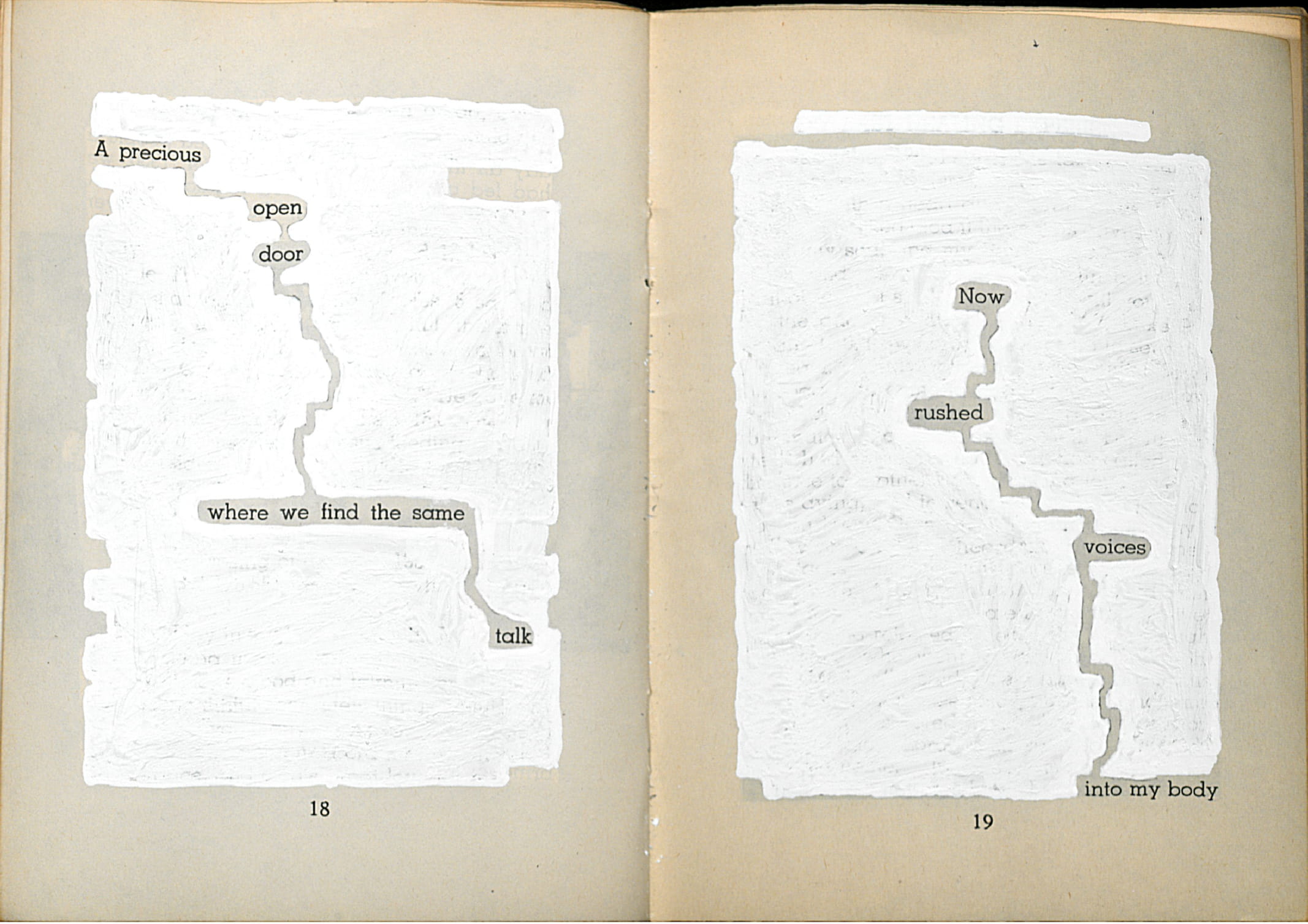

Like all genres, erasure is partially defined here by what it is not. Erasure is not “traditional poetry,” insofar as poetry has represented the linguistic expression of a single author’s feelings and thoughts. Erasures are not made of one speaker and one listener. Erasure is not pure, and its language is not original. Where there was a whole, erasure asserts a hole. That hole is felt as an absence, even as it becomes a container.

Let’s pretend that reading poetry is like sitting in the bay-window of someone else’s house: We are inside something, and from it we can view the external world, or turn around and look at the house we’re sitting in. Erasure, maybe, is that same window with its curtains drawn, so that only a little crack remains. We can’t see the entire countryside, but we catch a glimpse of a horse, grazing on what might be grass. Or we can see a few hairs of the horse’s tail. And the interior of the house has become a little darker. What is erasure?

Erasure is, principally, the sensation of being between not and is. An aesthetics of felt absence.

–

Poetry is a genre so accommodating and gluttonous that it will always unbuckle its belt, making room for a little bit more, broadening its definition. In Poetry magazine (and many other publications), you can now find a section called “Visual Poetry,” or something to that effect. This genre amuses and delights me. I think it suggests that poetry—once exclusively the domain of language—may not actually require words as its principal characteristic. We are always recognizing poetry as something else. That is one of the principal characteristics of poetry.

This is basically nothing new. In this, erasure resembles all the old thinking. Maybe we can even stop here and just say that erasure is a kind of collage, and plenty has already been said about collage.

But where concrete poetry makes “the sound and shape of words its explicit field of investigation” and usually involves an isolation of words from context, erasure builds a new context out of the original words.

–

Erasure might be the most literal manifestation of the creed (or is it a confession?), “I have nothing to say / and I’m saying it.” In order to be heard, the eraser does the opposite of speaking. By removing language, a paradox of production. Less is more.

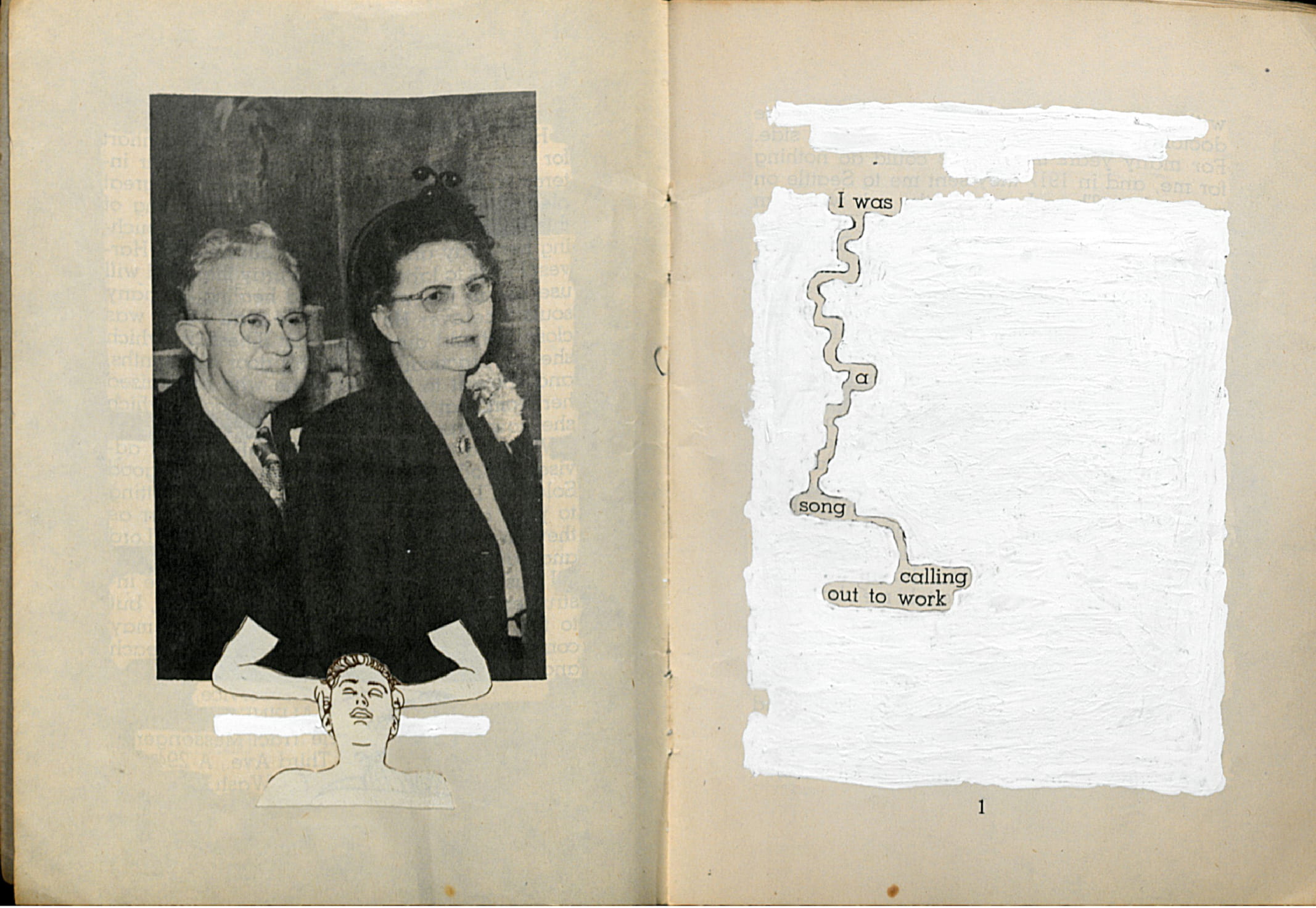

Entailing wordiness and wordlessness, erasure might be viewed as the poet’s “theory of other minds.” I can never make the erased text say exactly what I want to say. What was there to begin with will always assert its initial perspective in the way it constrains the words available to me. Therefore, the job of the erasure is to admit to, and navigate the difference between points of view.

Erasures always ask at least one question: How are we connected?

Often, the connection that compels the erasure is fraught. Something is wrong in the world. Most political erasures, like Niina Pollari’s blackouts of Form N-400, the Application for Naturalization in the United States, are compelled by indignation, anger. Their freight, or what’s being pulled along behind the new author, is a sense of helplessness, an urgent need to correct untrue language and reveal the true meanings behind it. We feel Pollari’s urgency in the thin gaps punctuating each blackout line, the difference in pressure and shade. There is a hastiness to the process, and it’s easy to imagine Pollari grabbing whatever was nearby—a Sharpie out of her desk—then printing out the application and delivering her payload. We can find a similarly urgent tone and process in the painful, funny blackout erasures of Isobel O’Hare. Take, for instance, O’Hare’s revision of Louis C.K.’s public apology: “My dick / is / a question / I / run from.” Enough said.

–

Maybe erasure is also an aesthetics of felt violence. A common objection to erasure comes from the view that it entails silencing the voice of another person, diminishing their thoughts, agency, intentions, and identity. And this is a reasonable objection. As a government and cultural practice, erasure is the most intuitive, routine strategy for asserting the importance of one group over another and for maintaining social hierarchies that privilege groups in power. In Orwell’s 1984, the protagonist’s job is to write new realities over the old ones, resulting in a destabilization of memory and a vacuum of social responsibility. Erasure as social control. This still terrifies me, but I argue that erasure can also be a practice of generosity. No form is bound to a single intention. See if you can erase even 10 pages of another person’s writing before you experience a kind of kinship, no matter how objectionable or ideologically opposite the content feels to you. This, too, terrifies me.

–

Ex ungue leonem: “(We may judge) the lion from its claw: from a part we may reckon the whole.” Or slantwise: Ex pede herculem. “(We may judge the size of) Hercules from his foot.” In both of these sayings, the translation into English requires that something missing be brought back into play. What is erasure if not a translation, and an honest one at that, for what’s left will never completely allow what’s gone from disappearing.

–

Why worry about erasure now? I could say something about how in the information age, erasure might be an exciting dam against the constant, rising streams of data. To erase a text and negotiate between another person’s language is much slower than making more language, and that slowness invites a sincere, unhurried interrogation of the self and others, putting the public-private binary of poetry to work. But as must be the case for most poems, the answer to “Why now?” is at least a little selfish. Why now? Because even when I talk about you, I want to talk about me.

I know for a fact that my mother is white, but my father was adopted and chooses not to disclose the identity of his adoptive parents. He says that he is Chinese, which would mean that I am one-half Chinese. But for all I know, he could be Vietnamese, or Filipino, or Japanese, or Korean, or Mongolian, or something else. This partial not-knowing about my identity has had all kinds of partially interesting consequences, including this essay.

I was raised in Arizona, near the border. I would say I identify more closely with Mexican culture than with Chinese culture. I also tan to an ambiguous brown, which is not a bad thing when you live near the border and you’re trying to blend in. I even went so far as to study Spanish, thinking I might completely adopt a self of my own choosing. The more I erased my family history, and in turn, my racial narrative, the more numinous I felt. I am happy for, and envious of people who have a deep connection to their heredity and to a single culture. At the same time, I am proud not to be one thing.

–

In a talk on the genreless genre of Noise, Bonnie Jones introduced her work by talking about her childhood. She said that she grew up on a traditional American farm, surrounded by livestock and siblings speaking a variety of languages. A veritable Babylon. Amidst the multilingual background noise of her adopted brothers and sisters, she called her experience “the most American upbringing” conceivable. In one of her live performances, And if I live a thousand lives I hope to remember one, Jones manipulates a cassette tape, describing the ensuing erasure this way:

The piece is constructed by manipulating in live performances a cassette player and a TDK EC-6M 6-minute looping cassette tape. The cassette player is used during the performance to create feedback by indiscriminately pressing the player’s controls (record, stop, forward, rewind). These six minutes are a recombinant document of numerous live performances over the past several years where I recorded, re-recorded, and erased the sounds of audio tape feedback, myself and other musicians.

To record, re-record, and erase. To hear the feedback as a desirable outcome, and not an unfortunate byproduct. Such a process recalls Joanne Kyger’s admonition to keep the typos in the writing. If my sense of self is dissolving, that is the beginning of a conversation. I am deciding every day what to erase, what to leave behind. To erase is to wield a power, to decide what your responsibility is to yourself and others.

–

Is it possible to speak of erasure without mentioning identity? Is it possible to speak of language without mentioning erasure? Ex ungue leonem. Erasure is language writ large. Allusion calls backwards to something both present and not-present. When Plato says writ large, he means the way the city-state reminds us of the citizen. Every person cannot be present in the judicial chamber, so one person stands in for the rest. When I teach figurative language in a poetry class, I find myself drawn back to the same few examples of metonymy, which are never misunderstood: The Crown, Nice wheels, White House. Lend me your ears.

Lend me your mouth.