Trash Elegies

(For Thirty Burros)

A generation ago, when Yucca Mountain was still being developed as a nuclear waste repository, the Warning Sign Design Contest convened in Las Vegas to exhibit possible installations that might deter people, present and future, from disturbing the radioactive garbage until it was safe. One Las Vegas artist proposed coating the land with layers and layers of human excrement: a mountain so disgusting, anyone who got close enough would vomit or shit themselves on sight. This would be a self-sustaining cycle of self-protection. The only problem was that all that fertilizer would just make the mountain more beautiful.

The debate over Yucca Mountain came toward the end of the United State’s decades long experiment with nuclear weapons. Between 1951 and 1962, the United States government conducted one hundred atmospheric nuclear tests at the Nevada Test Site, about one hour north of Las Vegas. Postcards and front pages from the fifties show mushroom clouds floating above the signs lining Fremont Street. One photo is framed by Vegas Vic, the forty foot neon cowboy, cigarette always lit in his lip. Here It Is! says the sign. Vic points his thumb toward the Pioneer Club Casino and the only cloud in the sky: a floating kernel of smoke, debris, and radioactive fission. The test was part of the Plumbbob series, which detonated atomic devices larger than the one dropped on Hiroshima.

During this series, servicemen dressed 1,200 real pigs in special-made outfits. They wanted to test the durability of cotton, nylon, polyester and military uniforms against thermal radiation. So they staggered the pigs at various distances from the blast site then measured which melted and what burned. Some reports say the soldiers were pretty attached to the pigs, that they got in the habit of feeding them treats, and that a few storms delayed the initial tests, so when it was time for the bomb to go off, the pigs could barely fit in their uniforms.

++

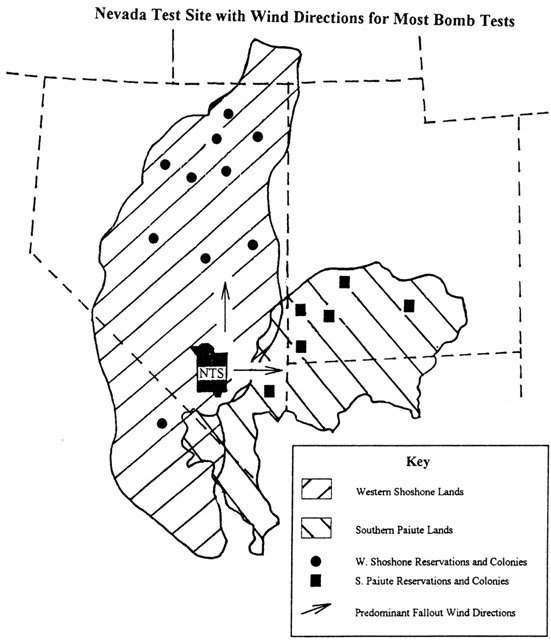

The Nevada Test Site sits on Newe Sogabia, the ancestral land of the Western Shoshone, who never legally or consensually ceded it to the United States government. Newe Sogabia stretches much of Nevada, and, like much of Nevada, is now quilted in blocks of federal agencies: the Bureau of Land Management, the National Park Service, the Forest Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Fish and Wildlife Services, the Department of Energy, the Department of Defense. More than eighty percent of Nevada is federally managed, more than any other state. This includes national parks, forests, and monuments, conservation land, tribal land, land subsidized for grazing and land dug into for mining. The land is called public, not because all of it is always open to the people, but because it is preserved and managed on their behalf – and with their tax dollars. Though more than a full fourth of the country is public land, that acreage is concentrated in the west, and the majority of Americans live at least one plane ride away from the land in their trust. This makes public land an experiment of the commons on a scale as wide as the nation.

Despite the harsh climate, the Nevada Test Site is home to a surprising array of plants and animals, says a report published by the Department of Energy. Surprising, I think, to an eye like mine, trained on deciduous trees and unused to seeing the way time works in the desert. I grew up east of the Mississippi, where only four percent of the land is public, and often green. Nevada averages less than ten inches of rain a year, and none of it ever reaches the sea. Within the Great Basin, any water that flows, falls, or melts is absorbed or evaporated. Tawny grasses bunch low, bighorn sheep cling to rock faces, and sage grouse emerge from under the brush just a few days a year. These are species that evolved to conserve. Nevada’s not flat, it’s never been bare, and I have to teach myself not to see it as empty. It’s hard to disentangle expansive from vacant. For a few centuries now, presidents have looked toward Nevada when they’re hoping to hide a national agenda in plain, public sight: the relocation of nations, open pit mines, atomic bombs.

The Nevada Test Site bridges two deserts, a transition landscape where sagebrush and coyotes join the Mojave and the Great Basin, linking creosote, rattlesnakes, juniper, pronghorn, burrowing owls, mountain lions, desert tortoises, kit foxes and golden eagles. None of these are pictured in the report. There’s only one animal photographed, just a few pages after the introductory maps, bombers, and mushroom clouds:

The small band of six horses is clear against the blurred ground, outlined like a stamp, all the edges inked clean. This is the same silhouette blazing football helmets and classic cars, the same shadow I’ve been following to and from Nevada for years. Wherever I am, the horse is a familiar shape in any unknown land. Maybe the authors of the report, dragging pixels across their screens in some satellite office of the Department of Energy, were relying on that. Even an untamed horse is recognizable. I’ve never had to train my eyes to this animal.

++

Every few months, I drive to the Northern Nevada Correctional Center for their wild horse auction. I take 80 east from California toward Reno, but I’m headed west, the catalog in my passenger seat. This Bald Faced Bay is a really cool and friendly little guy. Please take him to a great home as you will not be disappointed. He was gathered on October 19, 2021. The catalog lists the horse’s name, age, sex, height, weight, the range he was removed from, and a description of the horse written by the incarcerated man who trained him. Bud is a real good horse and will be a great addition to any home. He was gathered on October 7, 2021. There’s a picture of the horse and rider in profile, both parallel to the mountains behind them, and a close up of the horse’s head, cropped to the identification number on the left side of his neck freeze branded with an iron cooled by liquid nitrogen. Whatever color it was before the brand, the hair always grows back white. Chops is a quick learner and responds well when correcting his mistakes. The description is a few sentences about what the horse has learned so far, what kind of work he might be suited to, what a good boy he is. Big Bad Leroy Brown is obedient, has a great attitude and will make someone very happy. The brochure does not list the Offender ID assigned to each man by the Department of Corrections. Their name, age, sex, height, weight, conviction and sentence are public record online, but the catalog lists each man only as “Trainer.” Rocky is a very calm and loving horse and will be missed. In the pictures, a few men turn their heads to smile at the camera. McClintock has come a long way. All he desires is a home to call his own and a friend to be his pal for the rest of his life.

The Northern Nevada Correctional Center opens for the auction three times a year. The public is welcome; families fill the bleachers, sing the national anthem, pass a tray of cookies down the row, and watch the men show what the horses have learned in just one hundred and twenty days. The auction really starts before the bidding does, with the trainers in the saddle, the horses lined up at the fence, all their ears pointed toward the Carson range of the Sierras. Potential bidders walk up and down the line, auction catalog rolled in their hands, comparing the horse in front of them to the picture they’ve been studying. Bid winners will drive hundreds of miles and most will pay thousands of dollars for a horse they’ve never ridden. They're watching his gate and how he picks up a lead or bends to a leg. They’re also looking for something they can’t point to and won’t be able to prove: some combination of horses they’ve known and horses they’ve imagined. There’s just enough information for people to picture who the horse might be for them, and just enough unknown to dream about who they might be for the horse. The auction runs on all that’s possible in the untested relationship of the future.

Between conversations, the trainers sit quiet on the horse’s back. They comb the horse’s mane with their fingers and lean down to wrap their arms around his neck. After four months of training, this is their last day together. At every auction, at least three men tell me this horse is their best friend. Most of the time, the trainer says the horse’s name before they say their own: Blanco, Buddy, Big Tim, Socks, Speedy. I ask again: Ben, Brett, Jose, Matthew, Shane. They thank me for coming, they thank everyone for coming, thank God and the prison and the crowd for this opportunity. Surrounding the arena are twenty five corrals, a dozen round pens, and an array of alfalfa fields. The Northern Nevada Correctional Center holds more horses (and burros) than men.

The wild horse training program is one of the lowest paying jobs at the prison. The starting salary at the ranch is one dollar an hour, and goes up to $5.50. Half of any wages go back to the prison for room and board fees. For more money and fewer injuries, the men could also fix cars, sew clothes, bind books, upholster furniture, weld steel, build mattresses, or milk cows. The mattress factory pays $13, one dollar more than minimum wage in Nevada. But the horse training program is at least six days a week, always outside, always in view of the Sierras, so some men wouldn’t do anything else. Some men transfer from Ely or Vegas just to apply. A few trainers, like Shane, have been around horses their whole life, but most have never worked with horses before. They learn to ride as they learn to train. A horse sells for double, more often triple, what the man earned working with him. None of the money goes back to the trainers.

Shane writes poetry as he trains. He keeps scraps of paper in his jeans pockets for an idea here or there and writes out the rest back at his bunk. He can rhyme couplets for pages. Each line bobs along like a horse’s neck down the trail. The first poem Shane showed me was called “A Poem for the Chestnut in the Stead of a Home” about a horse that died of colic before the auction. Shane never names the horses he trains. Instead, he calls them by their colors: Dun, Roan, or Bay Horse. He says the names matter less to him than where the horse is going, and he wants people to be able to picture the horse as their own, and people just rename them anyway. A few people started coming to the auction looking for the horses Shane has trained in particular, and he often works with three or four at a time: one or two for the auction, another for the forest service or mounted police, one more for border patrol. He’s also started training the burros. He teaches them to follow a lead rope and drag a cart. He pets their long ears. The burros need a name for the auction catalog, and he can’t call them all “Gray,” so Shane enters them as some variation of “Jenny” each time, the colloquial name for a female donkey. When Shane talks about the burros, he refers to them exclusively as Princess.

++

In the decades since they declared them protected, the United States government has been wondering where and how to store wild horses (and burros). In 1971, when President Nixon signed the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act, any equine roaming public land was named “wild” and placed under the immediate jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management. Some had been untouched for generations. Some had recently been ranch horses or pets, lost or abandoned, too old, too expensive. All were descendents of a domesticated animal. Epochs ago, many species of horse evolved in North America; only one survived extinction by crossing the land bridge to Eurasia. When people met the horse, the animal changed the way we worked and warred forever, moving our languages and weapons across continents. In turn, we selected traits that made the best partner: endurance, strength, and obedience. Millenia later, Spanish colonial expeditions in the Americas brought the horse back to land that had long been without it. The grass was different, the big cats were gone, and the horse was now part of a human system, serving as both a weapon of subjugation and a tool of rebellion.

More than 70,000 horses (and burros) still roam Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. This 70,000 is both an estimate and a point of contention. The number itself shifts with each use of it, and doesn’t include the other herds also roaming state and tribal lands. If left untouched, the horse population can double in size every four years. This growing population challenges the mandate of the act, which not only stipulates protection of the horses, but also preservation of public land for multiple uses: conservation, recreation, grazing, lumber, and mining. Trying to meet that mandate, the Bureau of Land Management removes a set number of equines from the range each year. It is illegal to slaughter or export them, and less than five percent are adopted annually. So, in addition to those already roaming, some 60,000 more live in long term holding, untouched and unseen in off-range pastures where they are separated by sex and fed bales of federally funded hay for the rest of their lives. The average horse lives for about twenty five years. Burros can live up to fifty. More than two thirds of the Wild Horse and Burro budget goes to long term holding, and at $2 per animal per day, the bill to keep and feed them is already over one billion. The government is running out of room for the horses it is required to protect while the land runs out of forage for animals it never evolved to sustain. When I drive to the prison, I pass wild horses on the side of the highway. They don’t look up at the sound of my car. They look for water, they look for food, and I wonder what we are saving them from. Or what we are saving them for.

++

I never know where to put the burros. It’s the law that lumps them in, the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act, so they’re always named but never the subject. Burros don’t have a flowing tail. They’re more hardy than majestic. There aren’t as many statues or paintings of them, they have no history as a delicacy or as dog food. A burro doesn’t rear or gallop, it's not as easily ridden or rounded up, and they’re federally protected all the same. The logo for Wild Horse and Burro program is a profile of a burro’s head within the larger silhouette of a horse. The burro is made of negative space.

North of Yucca Mountain, within the blocks of federal land that include the Nevada Test Site, the Nellis Air Force Range, Area 51, and the Tonopah Bombing Range, is the Nevada Wild Horse Range, the first federally designated horse management area in the country. There are 176 other herd management areas across the ten states where horses still roam. The areas are not enclosed; they’re an approximation of where certain herds live across unique terrain, through different ecosystems, and with varied needs. The Bureau of Land Management estimates a certain number of horses (and burros) each management area can sustain, and 141 currently exceed that limit. These are more contested numbers, part of the criticism surrounding the BLM’s management and motives. What’s undisputed is that half the entire horse population is located in Nevada, and that Nevada is the driest state in the union, and that a healthy horse drinks five to ten gallons of water a day.

Due to its proximity to classified operations, the Nevada Wild Horse Range is the only herd management area unavailable to the public. I can’t visit or observe roundup operations there like I have elsewhere in Nevada, my legs so hot under the almost-shade of one juniper tree that a lizard fell asleep on my shin. Instead, all I can do is imagine the test site herds in the shadow of fighter jets. I picture them walking on ground that still rumbles. A history of the area, written by the nation’s largest wild horse advocacy group, reports: There are also a few burros who have wandered into this HMA, but they are not officially authorized to live on the land.

++

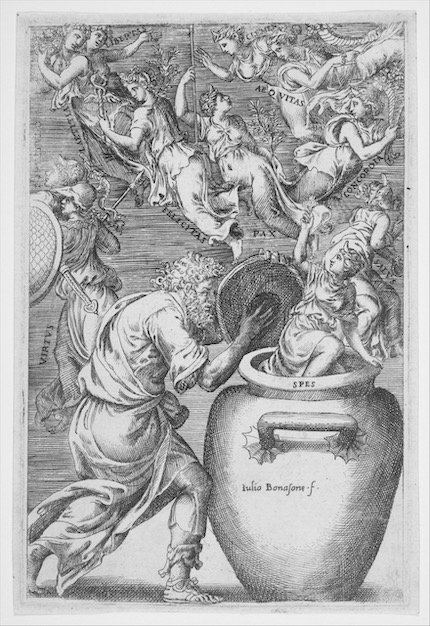

In the decades since they started generating it, the United States government has been debating where and how to store spent nuclear fuel and high level radioactive waste. Even before a repository site was chosen, the Department of Energy organized the Human Interference Task Force. Led by professor of semiotics Tom Sebeok, their objective was to create a message that would keep hazardous material buried for ten thousand years, alerting three hundred generations to the danger of nuclear waste. Plutonium-239 needs 24,000 years to become half as radioactive. It takes uranium-235 at least 700 million years to do the same. So “ten thousand years” was an understatement, but ten thousand years was a start. The official report was titled Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia, and their official conclusion was: you can’t do it. Materials erode and language evolves, so a sign is impossible. If there were people in two, five, or twenty thousand years, no plaque, barrier, or art would remain a reliable warning.

What we needed, decided the Task Force, was a relay system of recoding messages with a high degree of redundancy. In other words, humanity needed a myth. If we could tell a warning story, if a group could be entrusted to pass it down for generations, if the cautionary tale was vaguely moral, if the story shifted as language did, if it took the shape of its time, if it became enshrined in song, art, and idiom, if three hundred generations of people carried with them some sense of some warning from some story they’d heard so many times and in so many ways they couldn’t say for sure where it came from, if they heeded the warning anyway, if all of that, then we had a chance.

The legend-and-ritual, as now envisaged, would be tantamount to laying a "false trail," wrote the Task Force. Actual scientific knowledge of radiation and its dangers were unnecessary, as long as the myth prevailed. And how does a myth prevail? The Task Force wasn’t sure. The best mechanism for embarking upon a novel tradition, along the lines suggested, is at present unclear. But they did have one more recommendation. For dramatic emphasis, they suggested naming the small group of would-be myth makers an Atomic Priesthood.

A few years after the Task Force’s report, in 1987, Congress approved Yucca Mountain as a nuclear waste repository site. Other options included the Texas panhandle and the banks of the Columbia River in Washington. More rideline than peak, Yucca sits within the federal boundaries of the Nevada Test Site. It is sacred to both the Western Shoshone and the neighboring Southern Paiute, who have long called it Snake Mountain for the volcanic rings along its rocky spine. At multiple hearings protesting nuclear testing and the waste repository proposals, Shoshone spiritual leader and activist Corbin Harney described the life of the mountain and the snake inside. In 1990, Harney spoke at the International Citizens Congress for a Nuclear Test Ban in Kazakhstan. Yucca Mountain lies asleep like a snake, he said. When you walk on top of the mountain, it feels like you are walking on dried snakeskin. Someday, when we wake that snake up, a few of us will have to sit down and talk to that snake. It will get mad and rip open. When it awakens, we will all go to sleep. With his tail, that snake will move the mountain, rip it open, and the poison will come out on the surface.

There were 928 nuclear tests conducted in Nevada over the course of forty years. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the government admitted to the correlation between high rates of cancer in downwinder communities and others exposed to nuclear fallout. In the 1990s, the government began offering some compensation to those families who were aware of the offer and could fill out their application in English: $50,000 to downwinders, and $75,000 for those who worked on the atmospheric tests. These rates were never adjusted for inflation. The turn of a new century marked the height of the debate regarding nuclear waste storage at Yucca Mountain. Protesters flocked to public land, including members of the Western Shoshone. In 2002, the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles rejected a design for a new specialty license plate for Nevada. Submitted by state lawmakers, the plate featured a mushroom cloud rising over Las Vegas.

Around that same time, the DMV approved a different specialty license plate called Horse Power: a white stallion blazed against a dark blue sky, his mouth open, mane blowing, with hooves reared around the plate’s numbers. There are also two burros on the plate. They’re small and brown and blend in at the corner. Over the course of a decade, Horse Power raised one point three million dollars for a wild horse advocacy organization with the same name until that organization failed their second audit and the plates were discontinued. During production, Horse Power was made by an assembly line of incarcerated men from the Northern Nevada Correctional Center. Under each plate number, the men stamped the words Wild & Free.

Corbin Harney died of cancer three years before the government shut down the repository at Yucca Mountain. No radioactive materials are stored there. A five mile exploratory tunnel sits empty in the mountain, a second spine. There is still no designated, long-term storage solution for the United States’ radioactive waste. I do not know the half life of a myth.

I keep asking scientists to describe distinctions between invasive and native, wild and domestic, symbol and reality. I think I’m trying to delineate what I know and what moves me, but there’s no graph for that. And it’s not how myths work anyway. They spit out all the facts I feed them. They don’t like to be fixed to the page.

Last summer, an ecologist called me back from inside a yurt, a black and white cat traversing his lap. This particular ecologist is working to challenge invasive as a scientific category. He wants to demonstrate that the characteristics of introduced species are no more deleterious than the ones we call native, or at least he wants to call into question that whole classification, which is less quantitative than it is values-based, a vaguely moral human metric that runs along axes like heaven and hell, pure and tainted, sacred and pest. These are the kinds of calculations that compel us to cull starlings and remove ice plants, condemning the species we’ve brought with us, blaming their rampant propagation as if it’s unattached from our own. But if we didn’t see the eucalyptus lining California as bad because it has not always grown there, if we didn’t venerate nativeness like we venerate indigeneity, imbuing it with a hollow and selective kind of magic while we extract anyway, if we could learn about these ecosystems as they’ve inevitably evolved, if we could see how the species have met, fought, and helped each other, if we weren’t too busy sorting vines and rodents into Good Ones and Bad Ones to ask open ended questions about the way the world moves around us, then what could we know? Or that’s how I heard it.

So, the ecologist told me he found thirty donkeys, dead on abandoned farmland in the southwest. He called them donkeys because the name is regional and interchangeable, and one more way status eludes this animal. The ecologist was not too specific about the place because he’d technically found them while trespassing, so he technically can’t publish a paper on what he saw, but he said they could be here on this page. The donkeys were shot, he assumes, because they’re called invasive, an introduced species much like the horse but not exactly the same, brought back to the land where their ancestors evolved as a tool for colonizing it, under the legal umbrella of a protective mandate even though they're a different animal, and so have a different impact on the land. Donkeys don’t run in a herd. They scatter when scared, then find each other again. Their hooves and their mouths are smaller, their bodies less heavy, they tend to live in the drier, hotter deserts, and, he discovered through a separate and approved experiment of ecological observation, they dig wells. Donkeys make a hole in the ground to expose the water underneath and, when they’ve had their fill, they leave the hole behind, and other animals drink from it. Donkeys also, apparently, grieve with their shit. The ecologist was careful not to call the behavior “grief,” as he described the way the living donkeys returned to the property where their fellows had been shot. As the bodies decomposed, week after week, the still-living donkeys pooped on the flesh and then on the bones. The ecologist first called this a ritual. He corrected himself and said, “behavior.”

Thirty is so many donkeys. There were so many of them, and so much grief-pooping, filled with grief-seed deposits, that on top of the dead donkeys there started to grow little grief-gardens. Pockets of fertilized soil with seed varieties now growing where they would be otherwise absent from the stripped and deserted farmland.

++

Freezemark #21899125

Gather: Born at NNCC

Age: 3

Sex: Jenny (Female)

Height: 12 hands

Weight: 500 pounds

Trainer: Shane M▬

Jennifer is a sweetheart that leads very well! I can take her anywhere and she gets along very well with horses and other burros. She is super people friendly and has a dog as her good friend. She has loaded in every trailer that I have access to without any arguments. She is decent enough with her feet and she is quiet compared to most other burros. Jennifer has been ponied behind several of the horses and is a good friend that listens well and can keep a secret.

Shane grew up watching his family on the Shoshone side break horses. He says he took the animals for granted then, they were just always around, and there was always work to be done. He’s unlearned and relearned relating to animals, the work circling back to him. Another name for breaking a horse is to gentle it. Many of Shane’s poems are about the horses, or for them. Some orbit questions of land use and purpose, others are odes to mountains, to his dog. Once, folded into the envelope with a poem about money called “What It’s Worth,” Shane included his paystub from a fifteen day period. He worked all fifteen days, clocking in at 6:01, 6:11, 6:07 in the morning, and leaving 9.47, 9.38, 9.82 hours later. He earned $509.80 and could keep $254.90, but likely less than that. The last time I saw him was the auction in October, his last before he moved to transitional housing. Living there, he can join a construction crew and make at least minimum wage. He was sad to be far from the horses – for now. He’s saving up, he says, to buy back the last horse that he’s trained, a special sorrel, Sunny, the first one he’s given a name.

++

A few years ago, the Bureau of Land Management rebranded the roundups. Now, removing horses from the range, sometimes with the aid of a helicopter to herd them into temporary metal enclosures, sometimes baiting the horses with food and water, then separating stallions, mares, and foals, euthanizing those with chronic illnesses, untreatable conditions, or acute injuries, and treating a percentage of the females with birth control before releasing some back onto the range and loading the rest into a trailer to be quarantined then sent to long term holding is officially called a gather. As in, The gather is necessary because there is not enough water to support the number of horses in the area. And, The BLM plans to gather and remove approximately 800 excess wild horses. And, Due to the restricted access of the Nevada Test and Training Range, only those personnel deemed essential to the gather will be permitted to participate. The BLM publishes daily gather reports, including an inventory of the animals gathered, shipped, treated with birth control, released, and euthanized.

The 2018 records from the Nevada Wild Horse Range report 31 horses euthanized; 21 of them had a club foot, a tendon flaw that can render the hoof unwalkable and the horse lame. The causes of club foot in any horse vary depending on nutrition, exercise, and injury. The condition can also be genetic. Maybe coincidence, maybe fallout, there’s no way to know for sure. Twenty horses dead with club feet north of the Nevada Test Site isn’t proof of anything but the kind of paranoia that tries to make sense of bureaucracy. No burros were gathered. I still don’t know what to do with them, where to put the byproducts of my own research.

This morning I dug to the bottom of the wet garbage bag I’d filled in six days. Past used tissue (weeks), dried counter wipes (months), paper notices from the doctor’s office reminding me I’d signed up for paperless billing (years), cartilage on chicken bones (sixty days, should compost), noodles crusted to takeout container (four hundred years, shouldn’t order), and bubble wrap (is not recyclable). Down, down into one empty bottle of sunscreen, twelve daily contact lens cases, three bottle caps, two tin foil balls, slick saran wrap, crumpled post-it notes, and a disemboweled cat toy. A long receipt wrapped my wrist, the whole scroll coated in wet rice I’d fished from the sink drain the night before, and still I did not find my car keys.

I keep digging through piles of my country’s garbage as if, deep enough, I’ll find what I’m looking for. Some reason for generating it, or a creature I recognize. My hands are slimy and it stinks and at the bottom all I find is my own filmy outline. We are what we discard, and when I look at old gas masks, I see the elongated nose and the wide set eyes of a horse.

When the auction was over, I stood with Shane while the family that bought Jennifer pulled up their trailer. They had driven to Nevada just for her, looking for a companion to the old horse they’d just retired. Shane split off a piece of his oatmeal cookie for Sunshine, the stray dog who started following him around a few months ago. This is her donkey, he said. Sunshine trotted after Jennifer as she was loaded into the trailer. No struggle or complaints from the donkey, who walked right in and stood still as Shane tied the lead rope. Sunshine circled the truck, pawing at the door. I watched the dog duck under the whole rig, running back and forth between the wheels from one side to the other, while Shane stood to talk with the owners about where Jennifer was going (California), her training (ongoing), her preferences (carrots). Sunshine barked and I could see Jennifer’s long ears between the slats as the owners buckled their seatbelts and put the truck in gear. The dog wouldn’t move. Shane called her a few times, she ignored him, and he pointed under the shed at the side of the arena. There’s a rabbit under here! he lied, Come get it! The dog looked to the shed, to the burro, back to the shed, and ran to inspect it. The trailer started pulling out.

Sunshine abandoned the shadows under the shed and followed. The rig had to move slow, the driver checking for the dog in the rearview every couple seconds. She wouldn’t let anyone hold her still. Shane kept calling to Sunshine and Jennifer started kicking the trailer from the inside. The dog barked and ran after the truck as it picked up speed down the driveway. A Department of Corrections guard in a bulletproof vest wiped his eyes. Every fuckin time, he says, this dog gets her heart broke. Behind me, twenty more men watched the dog run down the road.

Images:

Life magazine’s picture of the week in June 1957 taken by Las Vegas News Bureau photographer Don English.

Picture from page five of the Origins of the Nevada Test Site history, written by Terrence Fehner and F. G. Gosling for the Department of Energy in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the site.

Photograph taken by the author at the Northern Nevada Correctional Center in June, 2023.

Epimetheus opening Pandora's box, an engraving by Giulio Bonasone (1531–76) reprinted in the Recommendations (And Related Considerations) section of Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia, a technical report compiled by Thomas Sebeok of the Research Center for Language and Semiotic Studies for the Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation in April, 1984.

Figure from the 2000 research paper The Assessment of Radiation Exposures in Native American Communities from Nuclear Weapons Testing in Nevada by Frohmberg, Goble, Sanchez, and Quigley.

Etching titled Je remarque avec ettonnement [sic] que le cheval …, by Max Earnst in 1938 for Leonora Carrington’s book The House of Fear.